An All-Ireland minor medal in 1968, a senior award in 1973 and a club junior championship memento last season.

An All-Ireland minor medal in 1968, a senior award in 1973 and a club junior championship memento last season.

Save Clare’s audacious breach of that which had been ordained to be since 1936, football at senior level down in Munster has been unashamedly incestuous in nature. The Godfathers of Kerry and Cork have, for over fifty years now, bred legions of children of God whose collective footballing talents have ensured that the country’s southern provincial crown has been a real family affair. The twin giants have dwarfed their neighbours’ achievements with a measure of comfort that has come nowhere near to being matched in any other province in the country in modern times.

Yet, almost paradoxically, such is the nature of gaelic games, that the long standing Godfathers of the game down south have been forced to share their parental duties of propagating that winning feeling. By definition, they have been forced to sit in the losers enclosure too. The Rebel county and the Kingdom have learned how to lose as well as win.

As a Corkonian with eight Munster championship medals to his credit, John Coleman, Millstreet’s ’erstwhile sporting maestro, knows all about the province’s power sharing arrangement. Few underage county footballers ever took such rewarding steps. For Coleman’s first four years on the national stage produced four All-Ireland medals and were it not for the ’oul enemy next door in Munster and some ill-luck, it might have been six on the trot.

As a fifteen year old with the shoulders of a nineteen year old, he stood on the terraces of Croke Park at the Canal End in 1967 and watched Cork minors hammer Laois in the All-Ireland final. The Millstreet Mob surrounding him that day faced the north with joy in their hearts. In almost the same manoeuvre, they faced young Coleman with a look that seemed to say “you should have been out there too”. Coleman, that hitherto minor trialist, failed to make the cut-off that year and took on board the aforesaid comments philosophically. His rationalisation would have its reward before the close of the following season. A burgeoning underage career would be handsomely embellished by two All-Ireland minor championship medals in the next two years in fact, 1968 and 1969. For the former, he lined out at centre half forward and linked up with club colleague Con Hartnett to defeat Sligo. In his last year at minor level, Coleman figured at midfield in a team (again including Hartnett) which beat a Mickey Moran-powered Derry side. Suddenly, the anguish of watching the aforementioned ’67 Cork minor triumph from the terraces didn’t put his emotions through the mixer quite as much.

John Coleman’s elevated status in the game ’cum 1969 was an arrangement made in heaven, via Millstreet National School, in effect. An arranged marriage organised by Mr Bill O’Keeffe NT, Messrs Coleman, Con Hartnett and Tommy Kelleher were choice material and O’Keeffe had designs on making them into show piece footballers. Back to back, under 14 county championships in 1964 and ’65, success carved out by the aforementioned trio and friends at Millstreet, lent the ultimate imprimatur to O’Keeffe’s teaching methods on the training field. Much the same crew were to form the backbone of the side which hauled in five consecutive Duhallow minor divisional titles in the years that followed the under 14 launch.

Younger brother of Billy of motor racing fame (still the only Irish driver to have won – 1974 – the British International Rally), John Coleman followed the family line and headed to Rockwell College in Tipperary to further his schooling. There, his gaelic football career suddenly, but not unexpectedly, took a nosedive in the confines of the traditionally hard-core rugby football nursery. With the infamous ban on foreign games in vogue at the time, a 1967 Munster Schools medal for the sporty outhalf wasn’t something the Millstreet youngster paraded on a daily basis but he was, nevertheless, justifiably proud of his achievement, an achievement which filled him with a burning ambition to pull on an Irish jersey onto his broad shoulders before or after securing his innate ambition of securing an All-Ireland senior medal. A pupil at Rockwell, along with other would-be notables such as Kildare footballer Hugh Hyland and R.T.E.’s Eamonn Lawlor, the scrapping of the ban in 1972 handed Coleman a fully recognised licence to exploit his versatile sporting talents to the full. Years earlier, however, he experienced an unnerving last couple of seasons at Rockwell after reneging on his rugby tutors in deference to Cork minor championship fever Pre-ban times were both turbulent and rewarding for the much in demand Millstreet athlete.

From the same stable out of which emerged such gaelic thoroughbreds as Denis Connors, Willie O’Leary, John Corcoran, Tommy Burke, Connie Kelleher and Denis ’Toots’ Kelleher, the second and last born to Paddy and Peg (nee Sheehan) Coleman of the town’s Mallow Road, automatically graduated to the county under 21 panel in 1969 and grabbed a Munster championship medal for his troubles. Better was to follow though. In 1970 and ’71 luckless Fermanagh surrendered their All-Ireland final under 21 claims to the Rebels. Millstreet clubmates Con Hartnett and Denis Long joined Coleman on the ’70 winning squad with Hartnett remaining on for the success in 1971 too. Captain of the under 21s in ’72, Coleman saw his hopes of a possible fifth consecutive All-Ireland medal dashed by the Kingdom. Millstreet’s high profile motor trade dealer was beginning to learn how to lose as well as win.

Adult inter county football with the Reds scooped, at first, a provincial junior championship medal to go alongside his 1971 underage All-Ireland souvenir. Within two years of junior glory, a prestige senior honour would make him a household name in Cork GAA circles. An approach by Highfield Rugby Football Club in Cork city would also heighten his profile in the local domestic sporting world and eventually lead to the realisation of a lifetime’s ambition.

A senior debutant with Cork in a national football league game versus Kerry in 1970 (O’Dwyer, O’Connell et al), the 5’ 10” and twelve and a half stone defender played on the Cork senior team beaten Offaly in the ’71 All-Ireland semi-final and the 1972 Munster final by Kerry. The taste of defeat didn’t sour his ambition, however, Coleman hung in there in the hope of ultimate glory. In 1973, Mount Everest was scaled. Millstreet went mad. Humphry Kelleher (full back), Coleman (centre half back), Con Hartnett (left half back) and Denis Long (midfield) were almost given the freedom of the town. Beating Galway in the All-Ireland final by 3-17 to 2-13 left the Millstreet quartet something akin to being folk heroes in the picturesque west Cork town.

Amazingly, within a year of figuring in Cork’s Croke Park heroics, a date with the famous New Zealand All Blacks team elevated the Millstreet colossus to heady new heights on the sporting front. Going down with his Munster colleagues by four points to thirteen to the men from the antipodes was no disgrace. In fact, for his efforts, Coleman, the Cork cavalier was rewarded the following season with an lreland B cap in a game against France at Landsdowne Road. For the centre three quarter, a linking with Labour Party leader elect Dick Spring in the rugby fare, excited and enthralled him, but combined with his efforts on the club and county football front, nearly burned out his batteries altogether. One of the codes needed to be dispensed with and the oval ball game was duly shelved, but not before he and his fellow Rebels won out Munster again in 1974.

1974 was to be a watershed for Coleman and co. however A sad one at that. The man himself describes the scenario most eloquent of all. “We played Dublin in the All-Ireland semi final that year but totally underestimated them. We were too cocky, bit the dust and in hindsight really made them (Dublin).” It was of little consolation to Coleman that Cork picked up the pieces just over a month late to beat the Dubs in front of over 30,000 fans at Croke Park in a National Football League clash of great significance to noon bar Cork really. Outgunning Brian Mullins that day at midfield was of little comfort to John Coleman either.

Married to Kerry lady Mary and father of Linda (18), Patrick (14), Marie (10) and Emma (9), John Coleman is unequivocal in his assessment of Cork’s decline thereafter. The extra time defeat to Kerry in the 1976 Munster Final was a turning point – “110 minutes of sheer tension, the like of which you couldn’t imagine” – and in effect, knocked the stuffing out of the Cork team for all time. The same spirit which had fuelled their 1973 triumph was gone. The Adidas affair of 1977 depleted the once all-enveloping spirit even further and for Coleman the 1979 Munster Final defeat was the cue to call it a day at county level, despite the fact that he was only 28 years of age. the ’oul zest and appetite had evaporated.

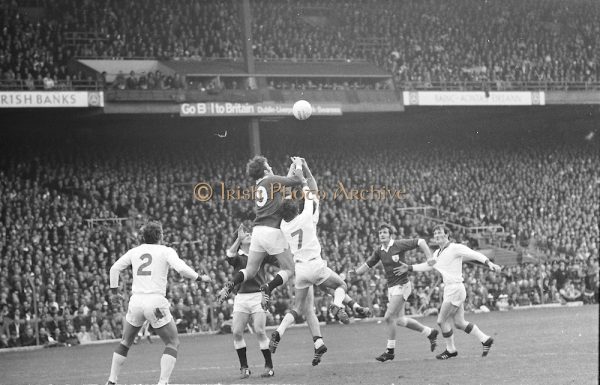

Galway captain Liam Sammon (no 9) and Cork’s Con hartnett (no 7) tussle for a high ball near the Cork goal. John Coleman awaits the breaking ball on the right

On the club front, Coleman toiled away religiously. He was always loyal, always leading from the front, but despite the best efforts of the likes of himself and Fr. Jim Kennelly, Dermot O’Shea and Tommy Burke amongst others, Millstreet fought a gallant but losing battle to do the business at senior level in Cork, from 1968 to the 1987/88 season, by which time they relinquished their senior status. Privileged to have played against the exceptionally talented Kerry team of 1975/76, he was forced to make do with his 1972 under 21 county championship medal as his sole tangible souvenir from his playing days with Millstreet until the season just gone by hearalded the arrival of a belated bonus. At 41 years of age, the one time flagship for the club resonated to the promptings of club trainer Patsy Barry and successfully steered Millstreet to junior championship honours.

Twenty years on from his All-Ireland senior medal success, John Coleman remains a folk hero in his native Millstreet. Still as affable as ever, as business like in the motor showrooms as he was on the football field. A monument to versatility and sociability, in fact.

from the Hogan Stand magazine 15th January 1993

========