Captain Paddy McCarthy

(8/Feb/1896-22/Nov/1920)

The late Paddy McCarthy was born at Rowels, Meelin and reared with his cousins, the Fitzpatricks of Commons, Freemount. He became an active member of Óglaigh na hÉireann following the 1916 Easter Rising, and was a member of B Company of the Second Battalion, Cork No. 2 Brigade of the IRA under Sean Moylan.

On May 8, 1918 he was charged with a gun offence and imprisoned for 18 months. He was held in Belfast prison where he took part in the hunger strike of 1918. He and others were transferred to Strangeways prison in Manchester where he made a daring escape with Austin Stack of Tralee and four others in 1919.

====

He took part in the capture of Mallow Barracks in September 1920, which was the only military barracks to be taken over in the war.

“It was planned that Willis and Bolster would enter the military barracks that morning in the normal way, accompanied an officer (Paddy McCarthy) of the column who would pose as a contractor’s overseer.

McCarthy, Willis and Bolster entered the barracks without mishap, their revolvers concealed. Members of the garrison followed their normal routine.

Inside the walls were Paddy McCarthy, Dick Willis and Jack Bolster, their revolvers concealed. Then Ernie O’Malley presented himself at the wicket with a bogus letter in his hand. Behind him and out of sight of the sentry were the other members of the main attacking party, led by Liam Lynch, Paddy O’Brien and George Power. When the gate was opened sufficiently, O’Malley wedged his foot between it and the frame and the soldier was overpowered. In rushed the attackers.

McCarthy, Bolster and Willis immediately went to the guardroom where they held up the guard. Realising what was happening, Sergeant Gibbs, rushed towards the guardroom in which rifles were kept. Although called upon to halt, he continued even though a warning shot was fired over his head. As he reached the guardroom door, the I.R.A. officer and one of the volunteers in the guardroom fired simultaneously. Mortally wounded, the Sergeant fell at the guard-room door.

By that time the majority of the attacking party was inside the gate. Military personnel in different parts of the barracks were rounded up and arms were collected. Three waiting motor cars pulled up to the gate and into them were piled all the rifles and other arms and equipment found in the barracks. In all some twenty-seven rifles, two Hotchkiss light machine-guns, boxes of ammunition, Very light pistols, a revolver, and bayonets, were taken away. The prisoners were locked into one of the stables, with the exception of a man left to care for Sergeant Gibbs. The whole operation had gone according to plan, except for the shooting of the sergeant.” [details]

====

Captain McCarthy met his fate on Mill Lane on the night of the 22nd November 1920, when his Flying Column took on the British Forces in Millstreet:

After atrocities on local residents by the Auxiliaries, the leaders of the Cork No. 2 Brigade column decoded to attack them on November 22nd 1920. William Reardon recalled: ‘When we had been in position for some time, there was no sign of any activity, but suddenly someone dashed past the end of Mill Lane, at the same time firing a shot. We rushed onto the Main Street at the junction with Mill Lane and opened fire on two Black and Tans who were running up the street towards their barracks. The enemy party escaped, but when we returned to Mill Lane, we found that Paddy McCarthy had been shot dead by the single shot.’

Paddy McCarthy is the first name on the monument in the Square. Annually the local Sinn Féin Cumann hold a commemoration in honour of his selfless dedication and service to his country.

For more, read the speach given at the 2006 commemoration by Jack Lane of the Aubane Historical Society.

======================

Paddy McCarthy – Died 1920

Born Meelin, Co. Cork. Shot dead at Upper Mill Lane, Millstreet on November 22nd. 1920 by Black and Tans. Had joined Volunteers immediately after 1916. Took part in Belfast hunger strike in 1918 under Austin Stack. Escaped from Strangeways Jail, Manchester in September 1919. Played decisive part in capture of Mallow Barracks and at Ballydrochane ambush, near Kanturk. Was buried with full military honours at Lismire, near Kanturk. – from Second North Cork Brigade

======================

Volunteer Patrick McCarthy of Meelin, Newmarket (Millstreet)

Date of incident: 22 Nov. 1920

Patrick McCarthy was ‘a leading North Cork fighter who played an important part in the capture of Mallow Military Barracks. A short time afterwards he fell in action in a fight at Millstreet.’ On 22 November 1920, Volunteers from the Millstreet Battalion and the column of the Cork No. 2 Brigade attacked the forces of the crown, which had been terrorising the nationalist population of Millstreet. According to Volunteer and column member Seán Healy, ‘the Black and Tan garrison in Millstreet were making themselves very objectionable to the public. They were visiting public houses, demanding and getting free drinks, smashing windows, and damaging doors. It was decided to teach hem a lesson, and so the column, in conjunction with members of local companies, who were acting as scouts, moved into positions in the town of Millstreet about 9 p.m. on 22nd November 1920.’ See Seán Healy’s WS 1339, 8 (BMH).

The decision by leaders of the Cork No. 2 Brigade column to attack the Auxiliaries recently arrived in Millstreet was prompted by the bombing of the house of Volunteer William Reardon and the attempted burning of the houses of Timothy Murphy and Mrs Lenihan on 20 November 1920. The Auxiliaries must have been anticipating such a reprisal. As one of the attacking Volunteers William Reardon, recalled, ‘When we had been in position for some time, there was no sign of any activity, but suddenly someone dashed past the end of Mill Lane, at the same time firing a shot. We rushed on to the Main St at the junction with Mill Lane and opened fire on two Black and Tans who were running up the street towards their barracks. The enemy party escaped, but when we returned to Mill Lane, we found that Paddy McCarthy had been shot dead by the single shot.’ See William Reardon’s WS 1185, 5 (BMH).

The IRA unsuccessfully sought to avenge McCarthy’s death: ‘Every night for the next week we moved into the town [of Millstreet], but the Tans made themselves conspicuous by their absence and confined themselves severely to the barracks. On the last night we went in, we brought the Hotchkiss [gun] into a dressmaker’s shop facing the barracks and fired a series of volleys into the barrack windows and door. They made no effort to come out.’ See Richard Willis and John Bolster’s WS 808, 25 (BMH).

McCarthy’s comrades removed his body to the house of Eugene O’Sullivan at Gortavehy, 5 miles away, where it was waked through the night and carried off for burial in Kilcorcoran Cemetery the next day. Liam Lynch personally took charge of the funeral arrangements. See Rebel Cork’s FS, 201. In the words of Seán Moylan, ‘It was an eerie experience following a coffin at midnight along lonely bye-roads from Millstreet to Kilcorcoran. And in spite of the secrecy with which the proceedings had to be veiled, the funeral cortege at Kilcorcoran had reached immense proportions. Men seemed to come from everywhere to pay their last tribute of respect to the dead soldier, and our loyal friend, Father Leonard from Freemount, came to say the last prayers at the graveside.’ See Seán Moylan’s WS 838, 147-48 (BMH). Almost two years later, McCarthy’s body was exhumed with extraordinary ceremony and reinterred in the family burial ground at Clonfert near Newmarket in October 1922: ‘The coffin lay overnight in his native church, Meelin, with an all day and night guard in relays. The funeral cortege was over three miles long. It reached from Clonfert to Meelin. The volleys fired over the grave were heard in Meelin, and the funeral procession was still moving out of the village.’ See Denny Mullane’s WS 789, 16 (BMH)

Seán Moylan, his close comrade, recalled McCarthy’s IRA career and personality: ‘Paddy McCarthy had been arrested after a battalion parade in March or April 1918. He was sentenced to eighteen months in Belfast prison. He participated in the strike there under Austin Stack. Afterwards he was transferred to Strangeways prison, Manchester, from which he escaped about September 1919. From the date of his arrival home in Ireland until August 1920, when he was selected as a member of the newly organised A.S.U., he had been associated with me in all activities. Now I was no more to see his friendly face, to hear his merry laughter, to have my spirits renewed by his unbreakable courage.’ McCarthy, declared Moylan, ‘had so much of dare-deviltry, was so infectiously gay and good humoured that he was an all-round favourite, and his death was the sorest blow that could be given to them [i.e., his comrades]’. See Seán Moylan’s WS 838, 147-48 (BMH). – [The Irish Revolution]

======================

“Do you remember our Quartermaster Paddy McCarthy? He was killed in a fight with Tans in Millstreet. Paddy O’Brien was wounded by an ambush of Tans near his own place. He ‘ s now Brigade Quartermaster. ” Paddy McCarthy was a loss. I thought of his unfailing good humour , his broad laugh and the lilt of song that would burst out at unexpected times. His quartermaster’s magic sack would no longer open to disgorge ammunition, cigarettes or mine batteries. – Irish Press 1937

=====================

The War of Independence in Freemount

In 1917 a company of the Irish Volunteers was formed in Freemount. As the company were in the Newmarket battalion area, they later became ‘B Company, Newmarket Batallion, Cork No.4 Brigade’.

In 1918 Sean Noonan a creamery manager in Freemount was arrested along with Paddy McCarthy, a native of Meelin who resided with his cousins, the Fitzpatricks of Commons. They were charged with possession of fire arms and both were sentenced to terms of imprisonment in Belfast Jail.

McCarthy was deported to Manchester prison from which he made a daring escape with Austin Stack of Tralee and four others. He then became a member of the Brigade Flying column and took part in the capture of Mallow Military Barracks, he was killed in a fight with the Black & Tans in Millstreet on November 22~ 1920… [Freemount Village]

======================

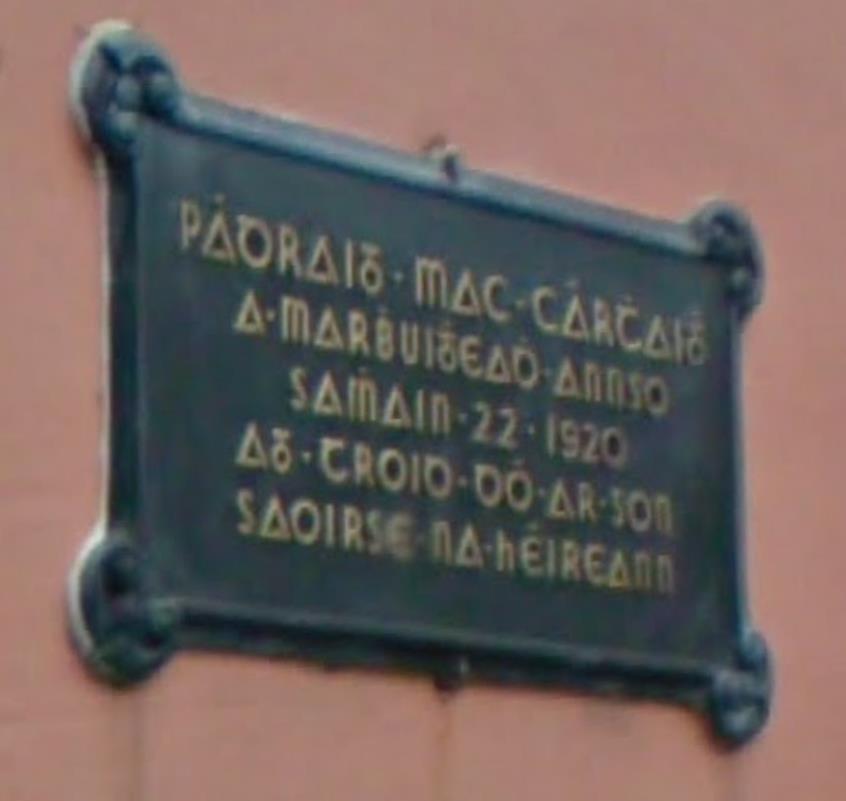

In 1947 a plaque was erected to Paddy McCarthy at the corner of Mill Lane and Main Street in Millstreet. He is commemorated there each year. [maps]

It reads: “Pádraig Mac Cárthaigh a marbhuigheadh annso Samhain 22 1920

Ag troid dó ar son saoirse na hÉireann”. (Patrick Mac Carthy was killed here on November 22 1920. Fighting for Irish freedom).

TODO: plaque unveiled at mill lane 1947 … where is the article that was being prepared?

======================

Paddy McCarthy is the first name on the monument in the Square.

======================

Named after him, Captain Paddy McCarthy Terrace is across from the Cannon O’Donovan Centre, back the Clara Road

=====================

There is a plaque to Paddy McCarthy directly across from the Church in Meelin [maps] [f]

=====================

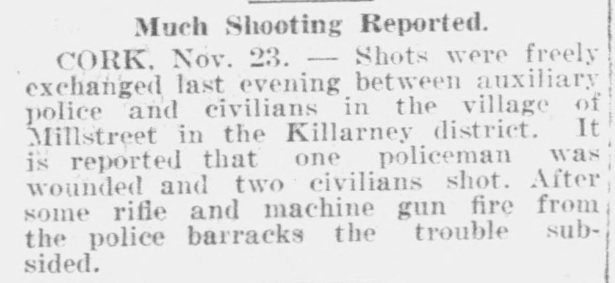

— The Brattleboro daily reformer., November 23, 1920

— The Brattleboro daily reformer., November 23, 1920

=======================

Paddy McCarthy story resembles Bugle

WHILE the central theme in Bryan McMahon’s play, ‘ The Bugle in the Blood’ deals with a son, Robby Trimble who is on hunger strike and the moral dilemmas coupled with the rights and wrongs of self sacrifice as seen through the eyes of his family.

While the play is set in Meelin by the Duhallow Players as part of the Meelin Rising Commemoration celebrations, there is an uncanny slice of history which resembles the play on home ground.

The director Michael O’Halloran who also plays a key role in ‘ The Bugle in the Blood’ uncovered a very appropriate Meelin connection with the subject mater of the play through the Volunteer leader, Paddy McCarthy, who was born in Meelin and joined the Volunteers immediately after 1916.

He was a key figure in the second Brigade IRA (North Cork) but it might not be generally known that he himself joined the hunger strike in Belfast in 1918 under Austin Stack.

He escaped from Strangeways Jail in Manchester in September 1919 and secretly returned to Ireland and made his way to O’Reilly’s undertakers in Newmarket which was a safe house.

Mrs O’Reilly, who is a grandmother of Michael, who runs the business today, was washing clothes in the back yard when she saw a very gaunt man make his way into a secret cellar underneath their house in Church Street.

McCarthy was so emaciated that she failed to recognise him, but she went to the door and gave an agreed knock – which he answered.

She then secretly and kindly fed and looked after him there in the following weeks, until his strength returned.

However, he was later shot in Millstreet and secretly buried at night in Kilcorcoran cemetery in Lismire. His body was later exhumed and there was a funeral mass in Meelin and he was buried in Clonfrert with full military honours.

The Bugle In The Blood which was presented by Duhallow Players in Meelin Hall, Sunday 24th and Thursday 28th to Saturday 30th April 2016 at 8pm.

[The Corkman ]

===========================

Escape from Strangeways Jail in Manchester

Piaras Beasley, in his book – “Michael Collins And The Making Of A New Ireland” – stated, regarding the escape from Strangeways Jail, Manchester, in October, 1919, that there was no effort to arrange an escape until he arrived, and that he started it. In this, Piaras Beasley has made a mistake. As a matter of fact, several, communications had passed between Stack, who was a prisoner in Strangeways Jail, and Collins about a possible escape. Eventually, it was decided that nothing would be done until Beasley was tranferred. there from Birmingham Prison. I was the first to take a note from Collins to Beasley; and his first remark to me was: “I am glad you have been busy here” – which showed there was previous contact.

At this time, Fionán Lynch, who was a prisoner also, was released; and he brought out a map showing the location of where a possible attempt at escape could be effected. Fionán was in close touch with Paddy Donoghue and myself; and we, of course, were working in close touch with Michael Collins.

At that time, of course, we had no friendly warders. All communications with the Manchester prisoners were mostly delivered by visitors. They were shown in to a room there. In shaking hands, they could transfer anything, or, as very often happened, in pots of jam and parcels of butter taken in by Mrs. Donoghue, The plan of the outside of the wall was sent in on a map, packed in a cake again.

This was done in Paddy Donoghue’s house. Rory O’Connor came to Manchester to examine the plans of the proposed escape. The code which was used was that Collins was “Ange1a”, and Paddy Donoghue was “Maud”. The six prisoners in Manchester at the time were Austin Stack, Piaras Beasley, D.P. Walsh, Seán Doran, Con Connolly and Paddy McCarthy, who was afterwards killed in an ambush. The plan was to hold up the warder during exercise; and we had got handcuffs, in case they were necessary, from Inspector Carroll of the Salford Dock Police, with, of course, the numbers rubbed out so that they could not be traced, The day of the proposed escape arrived, and it was found that the Volunteers from Dublin, under Rory O’Connor, missed some connection. The escape had to be arranged for a later date. The morning of the actual escape arrived. Miss Talty took in a watch to the prison. This watch had been sent out for repairs, but actually it was brought in to have the correct time recorded, so that there should be no hitch. The time would have to synchronise with that recorded on the watches outside – five o’clock.

As Beasley has pointed out in his book, I was unable to be present, because I was, at the time, laid up with an attack of the ‘flu. The street at the back of the prison led on to a croft; and this was mannedby a number of Volunteers from Dublin, Liverpool and Manchester, holding up all traffic and all pedestrians, including military. At the specified time, a stone was thrown over the wall from inside. This was the zero hour than, and a rope, leaded, was thrown over the wall from the outside. It only went a couple of feet over the wall; and it had to be hauled back again. The same thing happened the second time.

Eventually, Matt Lawless, a member of the Volunteers, walked up with an extension ladder and calmly put it up against the wall. Peadar Clancy mounted it, released the weight and threw over the ladder. The first man up was Stack. The second was Beasley himself; and when he had got to the top, two more had got to the bottom of the ladder; his hands got stuck; they were scraped and grazed; eventually he succeeded in landing on the ground. All six prisoners got out. Beasley and Stack were taken to a waiting motor car by Donoghue, and driven to the house of a man, named George Lodge, Bachelor of Science, and employed by the I.C.I. at the time.

Two of the prisoners, Seán Doran and Paddy McCarthy, were given bicycles, and in the excitement they missed their guide. They set off, one following the other – one thinking that the other was the guide – until they found themselves out in the suburbs. They did not know Manchester, and had no idea what to do. They went in to the F.C.J. (Faithful Companions of Jesus) Convent there. There was a conference of old members in progress. They told their tale. One of the ladies present was a Miss Josie O’Donnell from Rochdale; and she was advised to go and see the Parish Priest, Father Corkery. She told him her tale of woe – that she had the two prisoners, and did not know what she was to do with them. Where did he suggest that she could. go, but the place where we had Stack and Beasley staying – George Lodge’s. She brought the two lads – Doran and Paddy McCarthy – and left them waiting some distance away. She knocked at the door. It was an hour after the arrival of Stack and Beasley. When the door was opened, she said: “Are you Irish?” He said: “Yes”. She said: Are you a Catholic?” He said: “Yes”. She said: “Are you a Sinn Féiner?” He said: “No, no, not at all” – thinking of the men he had from Strangeways. So she said: “Do you know anybody in the Sinn Féin movement?” And eventually she asked him if he knew me. He said: “No, I never met him. Wait – I think his name was in the Catholic Herald at a meeting”.

He was not long gone when he came back, and gave her my name and address. George thought it was all lost and the plot was found out.

She came to our house with the two lads. They planked their bicycles’ some distance away. She knocked at the door. My wife answered the door and, although they went to college together, they did not recognise one another; they had not seen each other for a long time. The same questions were put again – “Are you a Catholic?” “Are you Sinn Féin?” My wife said: “We belong to the Self-Determination League”. So Miss Talty went out, and knew Josie very well. She told us what had happened, and that the two lads were outside. I had a brother-in-law, who was visiting me then because I had the flu, and I told him to take them up to his place until we arranged about them. They were taken to 64 Alexander Road – Seamus Talty’s place. – [Collins 22 Society]

========

James Hickey’s Bureau of Military History statement about the time of Paddy McCarthy’s murder:

“…At this stage Paddy McCarthy suggested that there was little likelihood of any more activity and “Neilus,” Healy proceeded to the junction of Mill Lane with Main St. to have a look round. As he reached the junction he noticed two people leaving Nicholson’s public house at the opposite side of the street. We returned immediately and reported accordingly. We were then about 20 feet from Main St., and as the message was being conveyed by “Neilus” Healy a shot rang out and Paddy McCarthy dropped. He had been shot through the head and was killed outright…”

==========

TODO: which RIC officers were responsible?