| Caoineadh Airt UÍ Laoghaire–Eibhlín Dhubh Ní Chonaill (ca 1743-1800)B’fhéidir gur aithris Eibhlín na dréachtaí seo os cionn an choirp i gCarraig an Ime.

Mo ghrá go daingean tu!

Lá dá bhfaca thu

ag ceann tí an mhargaidh,

thug mo shúil aire dhuit,

thug mo chroí taitnearnh duit,

d’éalaíos óm charaid leat

i bhfad ó bhaile leat.

.

Is domhsa nárbh aithreach:

Chuiris parlús á ghealadh dhom,

rúrnanna á mbreacadh dhom,

bácús á dheargadh dhom,

brící á gceapadh dhom,

rósta ar bhearaibh dom,

mairt á leagadh dhom;

codladh i gclúmh lachan dom

go dtíodh an t-eadartha

nó thairis dá dtaitneadh liorn.

.

Mo chara go daingean tu!

is cuimhin lem aigne

an lá breá earraigh úd,

gur bhreá thiodh hata dhuit

faoi bhanda óir tarraingthe;

claíomh cinn airgid,

lámh dheas chalma,

rompsáil bhagarthach –

fír-chritheagla

ar námhaid chealgach –

tú i gcóir chun falaracht

is each caol ceannann fút.

D’umhlaídís Sasanaigh

síos go talamh duit,

is ní ar mhaithe leat

ach le haon-chorp eagla,

cé gur leo a cailleadh tu,

a mhuirnín mh’anama….

.

Mo chara thu go daingean!

is nuair thiocfaidh chúgham abhaile

Conchúr beag an cheana

is Fear Ó Laoghaire, an leanbh,

fiafróid díom go tapaidh

cár fhágas féin a n-athair.

‘Neosad dóibh faoi mhairg

gur fhágas i gCill na Martar.

Glaofaid siad ar a n-athair,

is ní bheidh sé acu le freagairt….

.

Mo chara thu go daingean!

is níor chreideas riamh dod mharbh

gur tháinig chúgham do chapall

is a srianta léi go talamh,

is fuil do chroí ar a leacain

siar go t’iallait ghreanta

mar a mbítheá id shuí ‘s id sheasarnh.

Thugas léim go tairsigh,

an dara léim go geata,

an triú léim ar do chapall.

.

Do bhuaileas go luath mo bhasa

is do bhaineas as na reathaibh

chomh maith is bhí séagam,

go bhfuaras romham tu marbh

Cois toirín ísil aitinn,

gan Pápa gan easpag,

gan cléireach gan sagart

do léifeadh ort an tsailm,

ach seanbhean chríonna chaite

do leath ort binn dá fallaing —

do chuid fola leat ‘na sraithibh;

is níor fhanas le hí ghlanadh

ach í ól suas lem basaibh.

.

Mo ghrá thu go daingean!

is érigh suas id sheasamh

is tar liom féin abhaile,

go gcuirfeam mairt á leagadh,

go nglaofam ar chóisir fhairsing,

go mbeidh againn ceol á spreagadh,

go gcóireod duitse leaba

faoi bhairlíní geala,

faoi chuilteanna breátha breaca,

a bhainfidh asat alias

in ionad an fhuachta a ghlacais.

.

II

.

Nuair a shroich deirfiúr Airt (ó Chorcaigh) teach an tórraimh in aice Mhaigh Chromtha,

fuair sí, de réir an tseanchais, Eibhlín roimpi sa leaba. Seo roinnt den bhriatharchath a bhí eatarthu.

.

Deirfiúr Airt:

.

Mo chara is mo stór tú

is mó bean chumtha chórach

ó Chorcaigh na. seolta

go Droichead na Tóime,

do tabharfadh macha mór bó dhuit

agus dorn buí-óir duit,

ná raghadh a chodladh ‘na seomra

oíche do thórraimh.

.

Eibhlín Dhubh:

.

Mo chara is m’ uan tú!

is ná creid sin uathu,

ná an cogar a fuarais,

ná an scéal fir fuatha,

gur a chodladh a chuas-sa.

Níor throm suan dom:

ach bhí do linbh ró-bhuartha,

‘s do theastaigh sé uathu

iad a chur chun suaimhnis.

.

A dhaoine na n-ae istigh,

‘bhfuil aon bhean in Éirinn,

ó luí na gréine,

a shínfeadh a taobh leis,

do bhéarfadh trí lao dho,

ná raghadh le craobhacha

i ndiaidh Airt Uí Laoghaire

atá anso traochta

ó mhaidin inné agam?…

.

M’fhada-chreach léan-ghoirt

ná rabhas-sa taobh leat

nuair lámhadh an piléar leat,

go ngeobhainn é im thaobh dheas

nó i mbinn mo léine,

is go léigfinn cead slé’ leat

a mharcaigh na ré-ghlac

.

Deirfiúr Airt:

.

Mo chreach ghéarchúiseach

ná rabhas ar do chúlaibh

nuair lámhadh an púdar,

go ngeobhainn é im chom dheas

nó i mbinn mo ghúna,

is go léigfinn cead siúil leat

a mharcaigh na súl nglas,

ós tú b’fhearr léigean chucu.

.

III

.

Cuireann Eibhlín a mórtas as a fear céile in iúl go lánphoiblí sna dréachtaí seo. B’fhéidir gur aithris si an méid seo tar éis don chorp a bheith rétithe le haghaidh an adhlactha.

Eibhlín Dhubh:

.

Mo chara thu is mo, shearc-mhaoin!

Is gránna an cháir a chur ar ghaiscíoch

comhra agus caipín,

ar mharcach an dea-chroí

a bhiodh ag iascaireacht ar ghlaisíbh

agus ag ól ar hallaíbh

i bhfarradh mná na ngeal-chíoch.

Mo mhíle mearaí

mar a chailleas do thaithí.

.

Greadadh chúghat is díth

á Mhorris ghránna an fhill!

á bhain díom fear mo thí,

athair mo, leanbh gan aois:

dís acu ag siúl an tí,

‘s an tríú duine acu istigh im chlí,

agus is dócha ná cuirfead diom.

.

Mo chara thu is mo thaitneamh!

Nuair ghabhais amach an geata

d’fhillis ar ais go tapaidh,

do phógais do dhís leanbh,

do phógais mise ar bharra baise.

Dúraís, ‘A Eibhlín, éirigh id sheasamh

agus cuir do ghnó chun taisce

go luaimneach is go tapaidh.

Táimse ag fágáil an bhaile,

is ní móide go deo go gcasfainn.’

Níor dheineas dá chaint ach magadh,

mar bhíodh á rá liom go minic cheana.

.

Mo chara thu is mo chuid!

A mharcaigh an chlaímh ghil,

éirigh suas anois,

cuir ort do chulaith

éadaigh uasail ghlain,

cuir ort do bhéabhar dubh,

tarraing do lámhainní umat.

Siúd í in airde t’fbuip;

sin i do láir amuigh.

Buail-se an bóthar caol úd soir

mar a maolóidh romhat na toir,

mar a gcaolóidh romhat an sruth,

mar a n-umhlóidh romhat mná is fir,

má tá a mbéasa féin acu –

‘s is baolach liomsa ná fuil anois….

.

Mo ghrá thu is mo chumann!

‘s ní hé a bhfuair bás dem chine,

ni bás mo thriúr clainne;

ná Dónall Mór Ó Conaill,

ná Conall a bháigh an tuile,

ná bean na sé mblian ‘s fiche

do chuaigh anonn thar uisce

‘déanamh cairdeasaí le rithe –

ní hiad go lér atá agam dá ngairm,

ach Art a bhaint aréir dá bhonnaibh

ar inse Charraig an Ime!

marcach na lárach doinne

atá agam féin anso go singil —

gan éinne beo ‘na ghoire

ach mná beaga dubha an mhuilinn,

is mar bharr ar mo mhíle tubaist

gan a súiile féin ag sileadh.

.

Mo chara is mo lao thu!

A Airt Uí Laoghaire

Mhic Conchúir, Mhic Céadaigh,

Mhic Laoisigh Uí Laoghaire,

aniar ón nGaortha

is anoir ón gCaolchnoc,

mar a bhfásaid caora

is cnó bui ar ghéagaibh

is úlla ‘na slaodaibh

na n-am féinig.

Cárbh ionadh le héinne

dá lasadh Uíbh Laoghaire

agus Béal Atha an Ghaorthaigh

is an Uigdn naofa

i ndiaidh mharcaigh na ré-ghlac

a níodh an fiach a thraochadh

ón nGreanaigh ar saothar

nuair stadaidís caol-choin!

Is a mharcaigh na gclaon-rosc —

nó cad d’imigh aréir ort?

Óir do shíleas féinig

ni maródh an saol tu

nuair cheannaíos duit éide.

.

IV

.

Déanann deirfiúr Airt a caoineadh féin anseo. Nuair a luann sí, na mná óga

a bhí mór le Art, spriúchann Eibhlín.

.

Deirfiúr Airt:

.

Mo ghrá is mo rún tu!

‘s mo ghra mo cholúr geal!

Cé ná tánag-sa chúghat-sa

is nár thugas mo thrúip liom,

nior chúis náire siúd liom

mar bhíodar i gcúngrach

i seomraí dúnta

is i gcomhraí cúnga,

is i gcodladh gan mhúscailt.

.

Mura mbeadh an bholgach

is an bás dorcha

is an fiabhras spotaitheach,

bheadh an marc-shlua borb san

is a srianta á gcroitheadh acu

ag déanamh fothraim

ag teacht dod shochraid

a Airt an bhrollaigh ghil….

.

Mo chara is mo lao thu!

Is aisling tri néallaibh

do deineadh aréir dom

i gCorcaigh go déanach

ar leaba im aonar:

gur thit ár gcúirt aolda,

cur chríon an Gaortha,

nár fhan friotal id chaol-choin

ná binneas ag éanaibh,

nuair fuaradh tu traochta

ar lár an tslé’ arnuigh,

gan sagart, gan cléireach,

ach seanbhean aosta

do leath binn dá bréid ort

nuair fuadh den chré thu,

a Airt Uí Laoghaire,

is do chuid fola ‘na slaodaibh

i mbrollach do léine.

.

Mo ghrá is mo rún tu!

‘s is breá thiodh súd duit,

stoca chúig dhual duit,

buatais go glúin ort,

Caroilin cúinneach,

is fuip go lúifar

ar ghillín shúgach –

is mó ainnir mhodhúil mhúinte

bhíodh ag féachaint sa chúl ort.

.

Eibhlín Dhubh:

.

Mo ghrá go daingean tu!

‘s nuair théitheá sna cathracha

daora, daingeana,

biodh mná na gceannaithe

ag umhlú go talamh duit,

óir do thuigidís ‘na n-aigne

gur bhreá an leath leaba tu,

nó an bhéalóg chapaill tu,

nó an t-athair leanbh tu.

.

Tá fhios ag losa Criost

ná beidh caidhp ar bhaitheas mo chinn,

ná léine chnis lem thaoibh,

ná bróg ar thrácht mo bhoinn,

ná trioscán ar fuaid mo thí,

ná srian leis an láir ndoinn,

ná caithfidh mé le dlí,

‘s go raghad anonn thar toinn

ag comhrá leis an rá,

‘s mura gcuirfidh ionam aon tsuim

go dtiocfad ar ais arís

go bodach na fola duibhe

a bhain diom féin mo mhaoin.

.

V

.

De bharr constaicí dlí, dealraionn sé nár cuireadh Art i reilig a shinsear. Cuireadh an corp go sealadach;

agus cúpla mí ina dhiaidh sin, ní foldáir, aistríodh i go mainistir Chill Cré, Co. Chorcaí. B’fhéidir gur

chuir Eibhlín na dréachtaí seo a leanas lena, caoineadh ar ócáid an dara adhlacadh.

.

Eibhlín Dhubh:

.

Mó ghrá thu agus mo rún!

Tá do stácaí ar a mbonn,

tá do bha buí á gcrú;

is ar mo chroí atá do chumha

ná leigheasfadh Cúige Mumhan

ná Gaibhne Oileáin na bhFionn.

Go dtiocfaidh Art Ó Laoghaire chúgham

ní scaipfidh ar mo chumha

atá i lár mo chroí á bhrú,

dúnta suas go dlúth

mar a bheadh glas a bheadh ar thrúnc

‘s go raghadh an eochair amú.

.

A mhná so amach ag gol

stadaidh ar bhur gcois

go nglaofaidh Art Mhac Conchúir deoch,

agus tuilleadh thar cheann na mbocht,

sula dtéann isteach don scoil —

ní ag foghlaim léinn ná port,

ach ag iompar cré agus cloch. |

The Lament For Art Ó Laoghaireby Eibhlín Dhubh Ní Chonaill (ca 1743-1800)The extracts in this section appear to have been uttered by EibhIín over her husband’s body in Carriginima.

My steadfast love!

When I saw you one day

by the market-house gable

my eye gave a look

my heart shone out

I fled with you far

from friends and home.

And never was sorry:

you had parlours painted

rooms decked out

the oven reddened

and loaves made up

roasts on spits

and cattle slaughtered;

I slept in duck-down

till noontime came

or later if I liked.

My steadfast friend!

it comes to my mind

that fine Spring day

how well your hat looked

with the drawn gold band,

the sword silver-hilted

your fine brave hand

and menacing prance,

and the fearful tremble

of treacherous enemies.

You were set to ride

your slim white-faced steed

and Saxons saluted

down to the ground,

not from good will

but by dint of fear

– though you died at their hands,

my soul’s beloved….

My steadfast friend!

And when they come home,

our little pet Conchúr

and baby Fear Ó Laoghaire,

they will ask at once

where I left their father.

I will tell them in woe

he is left in Cill na Martar,

and they’ll call for their father

and get no answer….

My steadfast friend!

I didn’t credit your death

till your horse came home

and her reins on the ground,

your heart’s blood on her back

to the polished saddle

where you sat – where you stood….

I gave a leap to the door,

a second leap to the gate

and a third on your horse.

I clapped my hands quickly

and started mad running

as hard as I could,

to find you there dead

by a low furze-bush

with no Pope or bishop

or clergy or priest

to read a psalm over you

but a spent old woman

who spread her cloak corner

where your blood streamed from you,

and I didn’t stop to clean it

but drank it from my palms.

My steadfast love!

Arise, stand up

and come with myself

and I’ll have cattle slaughtered

and call fine company

and hurry up the music

and make you up a bed

with bright sheets upon it

and fine speckled quilts

to bring you out in a sweat

where the cold has caught you.

II

Tradition has it that Art’s sister found Eibhlín in bed when she arrived from Cork City for the wake in the Ó Laoghaire home. Her rebuke to Eibhlín led to a sharp verbal contest.

Art’s sister:

My friend and my treasure!

Many fine-made women

from Cork of the sails

to Droichead na Tóime

would bring you great herds

and a yellow gold handful,

and not sleep in their room

on the night of your wake.

Eibhlín Dhubh:

My friend and my lamb!

Don’t you believe them

nor the scandal you heard

nor the jealous man’s gossip

that it’s sleeping I went.

It was no heavy slumber

but your babies so troubled

and all of them needing

to be settled in peace.

People of my heart,

what woman in Ireland

from setting of sun

could stretch out beside him

and bear him three sucklings

and not run wild

losing Art Ó Laoghaire

who lies here vanquished

since yesterday morning?…

Long loss, bitter grief

I was not by your side

when the bullet was fired

so my right side could take it

or the edge of my shift

till I freed you to the hills,

my fine-handed horseman!

Art’s sister:

My sharp bitter loss

I was not at your back

when the powder was fired

so my fine waist could take it

or the edge of my dress,

till I let you go free,

My grey-eyed rider,

ablest for them all.

III

These lines, with their public adulation of Art, were probably uttered by Eibhlín after her husband’s body had been prepared for burial.

Eibhlín Dhubh:

My friend and my treasure trove!

An ugly outfit for a warrior:

a coffin and a cap

on that great-hearted horseman

who fished in the rivers

and drank in the halls

with white-breasted women.

My thousand confusions

I have lost the use of you.

Ruin and bad cess to you,

ugly traitor Morris,

who took the man of my house

and father of my young ones

– a pair walking the house

and the third in my womb,

and I doubt that I’ll bear it.

My friend and beloved!

When you left through the gate

you came in again quickly,

you kissed both your children,

kissed the tips of my fingers.

You said: ” Eibhlín, stand up

and finish with your work

lively and swiftly:

I am leaving our home

and may never return.”

I made nothing of his talk

for he spoke often so.

My friend and my share!

0 bright-sworded rider

rise up now,

put on your immaculate

fine suit of clothes,

put on your black beaver

and pull on your gloves.

There above is your whip

and your mare is outside.

Take the narrow road Eastward

where the bushes bend before you

and the stream will narrow for you

and men and women will bow

if they have their proper manners

– as I doubt they have at present….

My love, and my beloved!

Not my people who have died

– not my three dead children

nor big Dónall Ó Conaill

nor Conall drowned on the sea

nor the girl of twenty-six

who went across the ocean

alliancing with kings

– not all these do I summon

but Art, reaped from his feet last night

on the inch of Carriginima.

The brown mare’s rider

deserted here beside me,

no living being near him

but the little black mill-women

– and to top my thousand troubles

their eyes not even streaming.

My friend and my calf!

O Art Ó Laoghaire

son of Conchúr son of Céadach

son of Laoiseach Ó Laoghaire:

West from the Gaortha

and East from the Caolchnoc

where the berries grow,

yellow nuts on the branches

and masses of apples

in their proper season

– need anyone wonder

if Uibh Laoghaire were alight

and Béal Atha an Ghaorthaígh

and Gúgán the holy

or the fine-handed rider

who used tire out the hunt

as they panted from Greanach

and the slim hounds gave up?

Alluring-eyed rider,

o what ailed you last night?

For I thought myself

when I bought your uniform

the world couldn’t kill you!

IV

Art’s sister makes her own formal contribution here to the keen. Her reference to Art’s women-friends brings a spirited reply from Eibhlín.

Art’s sister:

My love and my darling!

My love, my bright dove!

Though I couldn’t be with you

nor bring you my people

that’s no cause for reproach,

for hard pressed were they all

in shuttered rooms

and narrow coffins

in a sleep with no waking.

Were it not for the smallpox

and the black death

and the spotted fever

those rough horse-riders

would be rattling their reins

and making a tumult

on the way to your funeral,

Art of the bright breast….

My friend and my calf!

A vision in dream

was vouchsafed me last night

in Cork, a late hour,

in bed by myself:

our white mansion had fallen,

the Gaortha had withered,

our slim hounds were silent

and no sweet birds,

when you were found spent

out in midst of the mountain

with no priest or cleric

but an ancient old woman

to spread the edge of her cloak,

and you stitched to the earth,

Art Ó Laoghaire,

and streams of your blood

on the breast of your shirt.

My love and my darling!

It is well they became you

your stocking, five-ply,

riding -boots to the knee,

cornered Caroline hat

and a lively whip

on a spirited gelding,

many modest mild maidens

admiring behind you.

Eibhlín Dhubh:

My steadfast love!

When you walked through the servile

strong-built towns,

the merchants’ wives

would salute to the ground

knowing well in their hearts

a fine bed-mate you were

a great front-rider

and father of children.

Jesus Christ well knows

there’s no cap upon my skull

nor shift next to my body

nor shoe upon my foot-sole

nor furniture in my house

nor reins on the brown mare

but I’ll spend it on the law;

that I’ll go across the ocean

to argue with the King,

and if he won’t pay attention

that I’ll come back again

to the black-blooded savage

that took my treasure.

V

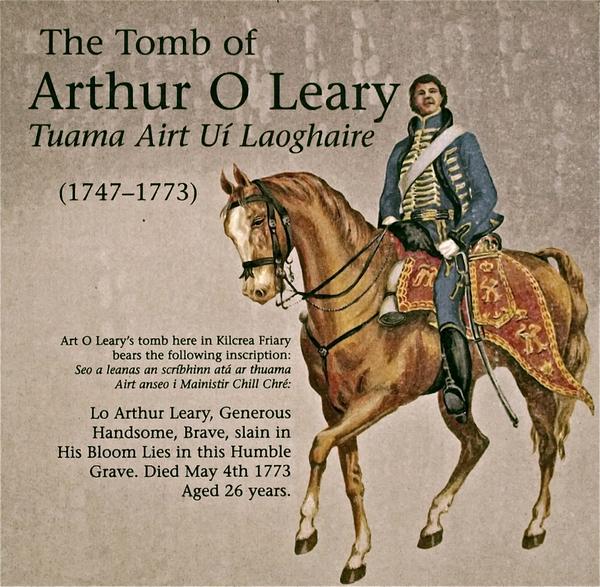

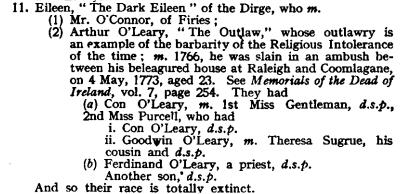

Due to some legal obstruction, the body of Art Ó Laoghaire was not buried in the ancestral graveyard, and temporary burial arrangements had to be made (in an alien grave just outside the old churchyard of Kilnamartyr, near Raleigh). It was possibly some months (or years) later that the body was transferred to the monastery of Kilcrea, Co. Cork. Eibhlín appears to have uttered the following passage of her lament on the occasion of the second burial.

Eibhlín Dhubh:

My love and my beloved!

Your corn-stacks are standing,

your yellow cows milking.

Your grief upon my heart

all Munster couldn’t cure,

nor the smiths of Oiledn na bhFionn.

Till Art Ó Laoghaire comes

my grief will not disperse

but cram my heart’s core,

shut firmly in like a trunk locked up

when the key is lost.

Women there weeping,

stay there where you are,

till Art Mac Conchúir summons drink

with some extra for the poor

– ere he enter that school

not for study or for music

but to bear clay and stones. |

Thank you for this very interesting article on Nóra Ní Shíndile a native of Millstreet, and a professional keener. I really enjoyed reading the history of the people and area. I have a way to go before I get to the end of the lament. Many thanks.

Another thank you for an interesting article!

Elizabeth, Christine, thanks. I learned a lot when i was putting it together … but what bugs me is that I grew up in Millstreet and we never knew much about it.

Our history lessons could have been so much more interesting and lively. We might have tried a bit of keening!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W9IuJDWJYEw

Above is a radio documentary called “The lost world of Art Ó Laoghaire”, which was inspired by the famous love poem Caoineadh Airt Ui Laoire written by Eibhlin Ni Chonaill.

—

This documentary sets out to see if Art’s death had less to do with being a show off and more to do with being one of the last efforts of a regressive Protestant Ascendancy in the summer of 1773.

Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire or the Lament for Art Ó Laoghaire was written by his wife Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill.

The epic poem is one of the greatest laments ever written, and one of the greatest love poems of the Irish Language. Eibhlín composed it capturing the life and tragic death of her husband Art on May 4, 1773.

It details the murder at Carraig an Ime, County Cork, of Art, at the hands of British official Abraham Morris, and the aftermath. It is one of the key texts in Irish oral literature.

The poem follows the rhythmic and societal conventions associated with keening and the traditional Irish wake (ceremony) respectively. The caoineadh is divided into five parts composed in the main over the dead body of her husband at the time of the wake and later when Art was re-interred in Kilcrea.

Parts of the caoineadh take the form of a verbal duel between Eibhlín and Art’s sister. The acrimonious dialogue between the two women shows the disharmony between the two prominent families concerned.

Produced by Aidan Stanley

An Irish radio documentary from RTÉ Radio 1, Ireland – Documentary on One – the home of Irish radio documentaries