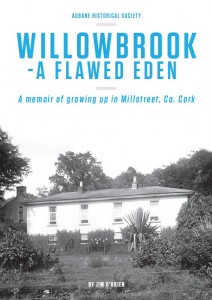

“Willowbrook – a flawed Eden. A memoir of growing up in Millstreet, Co. Cork” by Jim O’Brien is the latest publication from the Aubane Historical Society.

“Willowbrook – a flawed Eden. A memoir of growing up in Millstreet, Co. Cork” by Jim O’Brien is the latest publication from the Aubane Historical Society.

The author was evacuated with his brothers from London during WWII and they were sent to live with their aunts at Willowbrook House in Cloghboolabeg.

He paints a very vivid picture of his experiences at the house, of the people who owned and lived there and of those who worked there. He also gives entertaining pen-pictures of the local ‘characters’ he got to know. He describes them ‘warts and all’ and they are thereby made unforgettable.

Like all good stories it operates at many levels – the story of children separated from their parents and the effects this had on both; the issue of property relations within families and its consequences for individual members, particularly women; the relations between men and women, sexual and otherwise; the relations between adults and children; the class distinctions that were prevalent at the time and the consequences of this.

All the farm activities are well described with the attendant social activities that brought people together and showed the mutual interdependence that such a life entails despite all differences.

Hopefully, it will be on sale in Wordsworth’s for €15 by the end of the week…

A review by Tony Canavan in “Books Ireland” December 2013.

O’Brien was born in London to lrish parents who sent him to his mother’s relatives in Ireland, the Pomeroys, at the age of five when the second world ware broke out. He and his brothers spent the war years in a rambling house on a farm in county Cork. Although he spent his formative years there, this is no straightforward narrative but rather a series of reminiscences and observations of the author’s time in Willowbrook.

The strongest feature of the book is O’Brien’s ability to express himielf succinctly and pithity. This is particularly good in his description of society and local people. In one paragraph he neatly describes the stultified and stratified society that was independent lreland. The old Protestant elite was largely gone but the better-off Catholic farmers such as the Pomeroys slipped neatly on to the empty perch and were scathing about those beneath them. He is loud too at describing rural activities such as the slaughter and butchering of a pig, and the characters he encountered from a bawdy housemaid to his Uncle Nick’s cronies.

While the social observation may be what makes this book interesting to the general reader, the other side too is interesting in its own way. O’Brien gives the contradictory history of his family – the O’Briens were pro-union; the Pomeroys nationaiist – and how this affected family fortunes. He does not paint a very endearing picture of his lrish relatives, who come across as cold, selfish and scheming. All in all it’s hard to see any aspect of Eden in Willowbiook either inside or outside the house. There was little or no affection from his relatives and life outside could be brutal and hard.

Yet O’Brien also brings out the resilience and innate optimism of children. He and his brothers quickly adapted to their new life and took advantage of the freedom it offered. They soon became inured to the casual cruelty of agricultural life and the people who worked in it. Despite all the negatives he clearly looks back at his time in Willowbrook with fondness and hints that boarding school for instance was much worse. Being exposed to gore at an early age seems to have prepared him for life as a doctor also. The final section of the book, the return to London is imbued with regret at the resumption of normal life.

Willowbrook seems at first glance a small book, but it’s packed to the covers with stories written with wit and wisdom of a young boy’s early memories. Jim O’Brien, a resident of Big Harbour, has created a unique memoir through stories of growing up in Millstreet, Co. Cork, under difficult circumstances. O’Brien, along with his two young brothers, Dick and Nick, were sent away from home and parents during World War II. Fearing that London and other British cities would be reduced to rubble, the British Government ordered the evacu-ation of thousands of children shortly after declaring war on Germany in 1939. The majority were distributed to rural parts of England, but some were sent to North America, and some, like O’Brien and his brothers. were sent to relatives in neutral Ireland. The Pomeroy clan, to which O’Brien belongs, has a long, distinctive ancestry going back to Norman times. Willowbrook House belonged to O’Brien’s grandparents and was hequeathecl to his mother’s oldest unmarried sister, Margaret Pomeroy. Aunt Margaret hecame the boys primary guardian during those years. O’Brien describes in rich detail the di-chotomy of life, the social structure of classes, the upstairs and downstairs lives of the people who lived in a ‘Big House’ such as Willowbrook. Which of the daughters might inherit the family real estate may well depend upon the one who remained behind to care for ageing parents. She might also be the daughter having the least chance at mar-riage. The pressures on families to maintain social status, and obligations to kindred were stamped on their faces, and upon the mem-ories of a young boy in his formative years. O’Brien recounts the fortunes of his great-grandfather, Jeremiah Hegarty, a man of apparently obscure origin, who became the wealthiest man in the town of Millstreet. He had little when he arrived except his charm but wedded the daughter of the town’s wealthiest merchant. Hegarty in turn granted his daughter’s hand to Richard Pomeroy, the son of a local shopkeeper and O’Brien’s grandfather. Richard had little to offer except his connections to gentry. O’Brien suspects that Willowbrook House along with 57 acres of land was a wedding present from father to daughter. He says his grandfather’s greatest achievement seems to have been to marry a rich man’s favourite daughter, adding that “a lot of marginally competent men have achieved less.” There is another curious story that might easily be overlooked, tucked into the footnotes in the opening section Roots. O’Brien discovered a cousin, James Vincent Cleary, (1828 — 1898) who was the first Catholic Archbishop of Kingston, Ontario. O’Brien travelled to Kingston to visit St. Mary’s Cathedral in later life. The priests welcomed him, he being family, hoping he could shed some light on the final resting place of the Archbishop, as they themselves did not know. O’Brien found it odd that no one knew. The priests then took him to the basement of the Cathedral showing him a plaque on one of the many crypts dedicated to Elizabeth Minnitt who was the ‘faithful housekeeper’ of the Archbishop. A suspicion lingered that His Grace had perhaps hon-oured his celibacy obligation more in theory than practice, and the Archbishop’s remains were interred in the crypt with those of the aforementioned ‘faithful housekeeper’. If this was so, little wonder his burial place was kept secret given the scandal that would follow. “As an Archbishop His Grace must have been in line for a cardinal’s hat,” says O’Brien. “Did he die too soon, or did rumours of his suspected relationship with Miss Minnitt leak out and scupper his chances? If so, what a pity. An Archbishop perched on a branch of the family tree is not bad; a Cardinal something else entirely.” The house at Willowbrook was dis-tanced from the war in many ways, and the peaceful open spaces of the country-side during O’Brien’s childhood built a life-long preference for a natural life in the outdoors. He describes how this realiza-tion came home to him upon his return to his parents house. Though his aunts were stern and somewhat at arms length, he thrived in an environment with little supervision, having to appear only for meals, bedtime, and lessons, but otherwise free to roam the countryside as he pleased. By comparison, his mother’s tiny brick walled garden in the heart of London, being all the outdoor space he was afforded, appeared like a cage where he believed he would surely die. It was ‘a dreadful, heart-stopping, blood-chilling moment’, that he still recalls with absolute clarity. Throughout, the book is filled with wonderful stories that run toward question-able childhood adventures such as learning how to smoke, the hazards of bicycle racing, and how to best judge if the river is at a suit-able height for fording. Gypsies, and tinkers, and tinkers horses are all there, among a cast of unforgettable characters brought to life under O’Brien’s pen. For the most part light-hearted, but truthful to a fault, alongside searing revelations where young children are put to the test, this is an honest book written from the heart.

The above book review is by Mona Anderson in the Victoria Standard (a bi-weekly paper in Victoria County, Nova Scotia, Canada

An incredible journey – that’s the story of Dr. Jim O’Brien. Starting in London, England, he ping-ponged between there and Dublin and Canada, then ended up practising psychiatry in Cape Breton. But it wasn’t the circuitousness of his journey that was incredible. It was the strange things that happened along the way…

When he first came to Canada in 1965, after finishing med school in Dublin, he found himself working in Manitoba with an unusual man who caused him great stress. “It was difficult,” O’Brien recalls, “because he was an alcoholic.”

O’Brien then moved from the frying pan into the fire. The frozen fire. The Yukon. “In those days the sort of people who got jobs in the northern mines were …….

You can read the full interesting article (2002) on the author of Willowbrook at billrogers.ca/Bill_Rogers/OBrien.html

—-

Jim mentioned later that during his time as a carver in the 70s, he carved the sign over the Wren’s Nest pub in Dublin, and it’s still there forty years later.

See it on google maps:

https://goo.gl/RVgfQU