Lieutenant Colonel William MacCarthy O’Leary – the third son of Mr. John MacCarthy O’Leary, D.L. of Coomlagne, Millstreet, County Cork and Jane daughter of John O’Connell of Greenagh ( and widow of O’Donoghue of the Glens ) was born on the 6th January, 1849. Educated at Stoneyhurst College, Lancashire, he joined the 82nd Regiment, Prince of Wales Volunteers (now the 2nd Battalion South Lancashire Regiment), as an ensign in April, 1869, and became Captain in March, 1878, having previously filled the post of Musketry Instructor to the battalion for four years. In January, 1883, Captain MacCarthy O’Leary was appointed Adjutant to the 9th Lancashire Volunteers at Warrington, and with them he served five years, with advantage to the corps and great credit to himself, being equally respected by both officers and men. He was a thorough disciplinarian. He was appointed Major in August 1888, at the expiration of his term as Adjutant, and he was posted to the 1st Battalion South Lancashire Regiment (the old 40th), then at Portsmouth, and with them he served in Jersey, and at several stations in Ireland. In November, 1888, he was appointed to the command of the battalion, and in autumn of 1898 he took his corps to the manoeuvres at Salisbury Plain, where he was highly complimented on the efficiency and smart appearance of his men, and upon the skilful manner in which he handled them.

Lieutenant Colonel William MacCarthy O’Leary – the third son of Mr. John MacCarthy O’Leary, D.L. of Coomlagne, Millstreet, County Cork and Jane daughter of John O’Connell of Greenagh ( and widow of O’Donoghue of the Glens ) was born on the 6th January, 1849. Educated at Stoneyhurst College, Lancashire, he joined the 82nd Regiment, Prince of Wales Volunteers (now the 2nd Battalion South Lancashire Regiment), as an ensign in April, 1869, and became Captain in March, 1878, having previously filled the post of Musketry Instructor to the battalion for four years. In January, 1883, Captain MacCarthy O’Leary was appointed Adjutant to the 9th Lancashire Volunteers at Warrington, and with them he served five years, with advantage to the corps and great credit to himself, being equally respected by both officers and men. He was a thorough disciplinarian. He was appointed Major in August 1888, at the expiration of his term as Adjutant, and he was posted to the 1st Battalion South Lancashire Regiment (the old 40th), then at Portsmouth, and with them he served in Jersey, and at several stations in Ireland. In November, 1888, he was appointed to the command of the battalion, and in autumn of 1898 he took his corps to the manoeuvres at Salisbury Plain, where he was highly complimented on the efficiency and smart appearance of his men, and upon the skilful manner in which he handled them.

Thence the 1st South Lancashire moved to Preston, where they became distinguished by their prowess on the football field, and in 1899 the battalion won the Army Cup. The warm reception given to the team at Preston on bringing home that trophy is still remembered. While in service at Preston, Lieutenant Colonel O’Leary had an opportunity of renewing his acquaintances with the 1st Vol. Batt. South Lancashire Brigade, in which he was always interested, and it was a source of much gratification to him to be asked to present the annual prizes to the members of the corps in December 1898, when he met many old friends.

Lieutenant Colonel O’Leary married, in 1878 – Mary daughter of the late Mr. Hefferman Considine, of Derk, County Limerick, and had three sons and two daughters. The eldest son John was a Lieutenant in his father’s regiment, the 1st South Lancashire’s, and served in India. The second son Heffernan William Denis, known as Donogh – also served his Majesty as a Second Lieutenant in the 87th Royal Irish Fusiliers and won the DSO and MC

On the death of his father in 1896, Lieutenant Colonel William O’Leary succeeded to the family estate and in 1897 he was appointed a Deputy-Lieutenant of his native county of Cork.

Soon after the declaration of war in 1899 – he took part with them in most of the engagements for the relief of Ladysmith. At Pieters Hill, on the 27th February, 1900, the South Lancashire’s much distinguished themselves. They carried the hill, and opened the road to Ladysmith, as General Sir Redvers Buller reported in his dispatch of February 28th; “The main position was magnificently carried out by the South Lancashire’s about sunset.”

But in this final and successful attack, Lieutenant Colonel O’Leary was shot dead – close to the enemy position while leading his men to victory. The World of the following week wrote:- “It would be impossible to exaggerate the feelings of sorrow with which all ranks of the 1st Battalion South Lancashire Regiment will have laid the remains of their much loved commanding officer to rest after the last days fighting for the relief of Ladysmith. Lieutenant Colonel O’Leary was one of the most popular commanding officers of the whole service. He was a trusted friend of every officer, non-commissioned officer and man serving under him, entered into all their sports, and never thought of sparing himself where the interests of his Battalions were concerned. Though one of the tallest men in the army, he was also the most active, and it was largely due to his encouragement of sport that the 1st South Lancashire had established such a reputation for themselves as cricket and football players, in both of which games they excelled, as Lieutenant Colonel O’Leary needed to say, with true Irish humour, “the old 40th should.”

He was twice mentioned in dispatches for his services

L. G. February 8th 1901 by General Sir R Buller who refered to Lieutenant Colonel MacCarthy O’Leary as a great loss that the country sustained by his death.

![Remember, men, the eyes of Lancashire are watching you today!" This depiction of the moment when the South Lancashires swept over the Boer trenches on Pieters Hill was painted by J.A. Lamb, who as a private soldier in the regiment was there. [ref]](http://www.millstreet.ie/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Boph-lamb.jpg)

==========

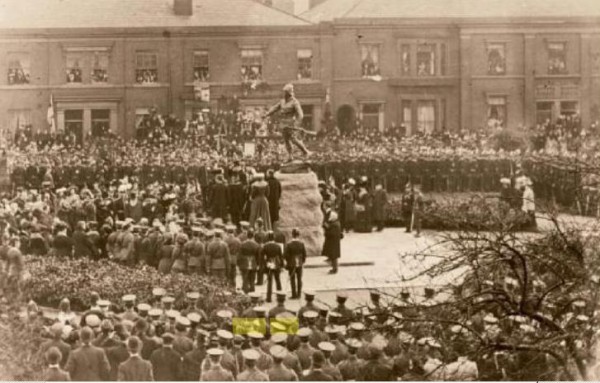

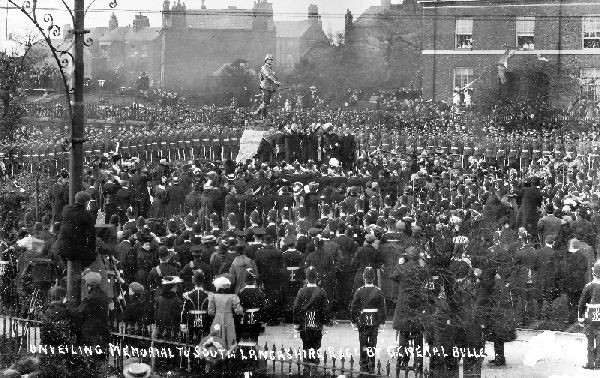

Statue of Lieutenant Colonel McCarthy O’Leary (War Memorial)

Sculptor – Alfred Drury

Unveiling – 21 February 1907

Place – Egypt Street Warrington

Precise Location – at the centre of Queens Gardens

Lieutenant Colonel O’ Leary is represented in uniform appearing to stride forward. His right arm is shown outstretched in front of him and contains a pair of field glasses, his left hand clutches a rifle by his left side. His gaze is shown right of centre and slightly upwards. Relief of a mourning family alongside a dead soldier lying on a bed with an angel by his head. According to a writer in The Dawn, the likeness is said by those who knew the Colonel best, [that] the artist has succeeded in endowing it with that touch of grandeur and imagination which are so often lacking in statues of this sort

Queens Gardens (along with the nearby Victoria Gardens) were open in 1896 and dedicated on 3rd April 1897 in commemoration of the borough’s Incorporation and Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. The statue was unveiled on 21st February 1907, a few years after a nearby street had been named O’Leary Street [map]. This was an honour bestowed upon one man – the statue was erected to commemorate the courage of volunteers from Warrington and Lancashire, and other soldiers of the Prince of Wales’ Volunteers who fought in the South African War. The gardens occupy the centre of the square and were laid out in 1897.

The granite and statue were placed by the Borough Surveyor. Before the unveiling ceremony the statue was hidden from view by a huge Union Jack Flag. The unveiling of the statue was preceded by a Requiem Mass at St. Mary’s church, attended by the Mayor and the town council. At a quarter to twelve a procession of mounted Volunteers, Colonels and General Buller moved up Bridge Street and Sankey Street to the Town Hall. Here, it was met by the chairman of the War Memorials Committee, the Mayor, Committee and Town Council. The procession then continued to Parr Hall for a luncheon in the General’s Honour. From here, the group moved as best they could through the crowded streets to the Queen’s Gardens. The ceremony itself appears to have been filled with pomp and circumstance. A military square, four sides lined with soldiers from the regiment, acting as the Guard of Honour with their flag, bearing the names of famous victories.

Within the square stood the two sons of Lieutenant Colonel O’Leary, a blaze of officers, members of the War Memorial Committee and their wives; beyond them gathered a group of veterans with friends and subscribers; beyond these, the crowd thronged to get a better look at the proceedings. Henry Roberts, the chairman of the War Memorial Committee called upon General Buller to unveil the statue. The artist, Alfred Drury, handed him the white cord and to a burst of cheers the covering fell from the statue. There was a grasp of amazement from the crowd. The crowd began to sing, ‘When our heads are bowed with woe’, which merged with the band’s ‘The Last Post’. Many speeches followed, with the mayor describing it as ‘the very noble monument’

=======

A CATHOLIC OFFICER.

At a time when Catholics are lamenting the death of that promising young officer, Lieutenant Miers, our readers will find of interest a lecture delivered by Father Hayden, S.J., the rector of St. John’s, Wigan, on the life of Colonel McCarthy O’Leary, who was killed in action whilst commanding the 3rd Battalion Manchester Regiment, with the Ladysmith Relief Force.

Father Hayden said : Ladies and gentlemen, we live in stirring times, remarkable events are taking place with startling rapidity in every direction, and such is the perfection to which the agencies for spreading information have been brought, that we have scarcely received and digested one item of news, when another comes and claims even closer attention. And so no wonder that so many complain of sleepless nights when the brain all day long has been simply bewildered with the succession of startling and engrossing topics, acquaintance with which is almost necessary if we wish to be considered up-to-date. To travel back no further than twelve days several things of surpassing interest to us as Britons and as Catholics have taken place, any one of which might have supplied us with ample subject matter for the lecture, or the paper, I have been invited to give to the members of the Christian Doctrine Society. May I mention three very briefly : A Catholic priest, Father Barnes, has just published a remarkable book on the much discussed subject of St. Peter and Rome. And so ably and thoroughly has he done his work, that one of the most scholarly of the London newspapers confesses that now no longer can Protestant disputants venture to deny that St. Peter laboured in and was martyred in Rome 1 This, I repeat, would have been a suitable and tempting subject to read a paper on. We had hardly got over our surprise at this sudden abandonment of a long occupied position by our non-Catholic friends, when from another quarter comes an announcement that almost takes away our breath—the Queen gives permission to all soldiers serving in Irish regiments to wear sprigs of shamrock in future on St. Patrick’s Day. As Patrick is my own name, and as I am a humble follower of a Soldier Saint, I may be permitted to express my extreme satisfaction at this concession to my comrades. Once again the telegraph wire flashed the news that her Majesty, with her wonderful tact and her wonderful talent for doing the right thing at the right moment, not content with allowing her Irish soldiers to wear the long forbidden shamrock, contemplated-in the near future a visit to the land of the shamrock. It seemed too good to be true. That the Queen should after the lapse of a whole generation, at a season of the year, and at a time of her lite when nobody but she could dream of such an enterprise, once more visit Ireland, I say again it was too good to be true ! And what, pray, prompted her Majesty to perform such a gracious act ? Surely nothing but the desire to show that she spoke earnest words and sinceie words when complimenting through the general, on the field of battle, her Irish soldiers on their splendid bravery. And, ladies and gentlemen, after this somewhat lengthy preface, I come now to the subject of this little paper, to one of these Irish soldiers of the Queen, who, alas, has left us, Colonel William McCarthy O’Leary. It is not my intention to give anything like an adequate account of the life of Colonel McCarthy O’Leary, as has been announced in etror. I am not competent to do so, having only had the pleasure of knowing him for about two years. But I saw so much to admire in him in that time that I resolved on that sad night last week when I saw his name amongst the slain that I would not keep to myself certain things the knowledge of which would edify others and possibly move to imitation. I am, of course, not unaware of the danger of falling into the language of exaggeration that a writer is exposed to who has a very deep affection for his hero. And for this reason I am careful to use here only adjectives and expressions found in the press notices of the gallant officer’s life and death. First of all, then, let us see how much, or rather how little, the world through the newspapers, has to say about Colonel O’Leary, and then allow me to add a few things not to be found in the papers, though known to many of his friends and people among whom he lived, things that may be useful and helpful to some, and must be of interest to all. William McCarthy O’Leary was born on January 6, 1849 in Cork. He was the the third son of Mr. John McCarthy O’Leary, a former high sheriff of county Cork. The Colonel himself was a Justice of the Peace of Cork, and also an Under Sheriff. He entered the army in 1869, joining the 2oth Foot, now the 2nd Battalion of the South Lancashire Regiment. He received his lieutenancy in 1872, and from 1874 to 1878 was instructor of musketry. in 1878 he was promoted to a captaincy. He was gazetted major in 1883, and until 1888 acted as adjutant to the auxiliary forces. He was appointed lieutenant-colonel in 1896, and completed 30 years of service in the army in April. So, under the rules of the service, he was on the point of retirement, and was only afraid the war would be over before he reached South Africa with his regiment. This, ladies and gentlemen, is the newspapers’ short summary of the man, and we do not look for any more from the newspapers. One of these newspapers says he will be remembered for his splendid physique, being the tallest man in his regiment ! I venture to say Colonel McCarthy O’Leary will be remembered for more than that ! None of the things I have recounted to you from the papers will explain the sorrow his death has spread around. The whole British Empire seemed to go beside itself with joy when the news came of the relief of Ladysmith. Shall we ever forget the scenes of wild enthusiasm here in the streets of prosy Wigan on that day? Like magic, flags popped up and out from the most unexpected quarters. Factory hands took French leave, and paraded the town singing “Soldiers of the Queen” in a way that much-sung song was never heard before. Tiny children made frantic efforts to keep up with their longer legged companions as they swung through the streets cheering and shouting during dinnertime from every school. Suddenly in two Lancashire towns all is changed. The joy bells are hushed, the streets are silent, the flags all drop to half-mast—a gloom settles over people who recently were so hilarious. Major Hall, the second in command of the South Lancashire Regiment, has wired to a newly made widow, “Regiment sends heartfelt sympathy. Colonel shot dead whilst gallantly leading charge.” Surely no ordinary man it was whose death so quickly changed joy into sorrow. No he was no ordinary man. Colonel McCarthy O’Leary was, in an eminent degree, a credit to his country, his profession, and his creed. A credit to his country—he knew how to be an ardent patriot without abating one jot or tittle of his love country and her honour, and occupy with distinction the position of commanding officer of an English regiment. In one of these letters before me, written probably in the presence of a crowd of English officers in Preston, he speaks of himself as “a soldier who hails from the dear old county of Cork.” He was a warm’ hearted, and not a hot-headed Irishman, and deep was his scorn for the coward who was born in Ireland, and sought to pass under a changed or mutilated name as an Englishman. He loved his country, loved to think about its history and its prospects, its music and its poetry. And here I may tell you about a little scheme of mine that cannot now come off, with which be was associated. I was determined this year to honour the feast of St. Patrick at St. John’s in special way, as I believe the Superior at present is the first here whose Christian name is Patrick. At Stonyhurst College last August we discussed the matter, and by his permission and influence we should in all probability have had the fine band of the South Lancashire Regiment here this week at the Drill Hall, and Captain Kenna, V.C., promised me if he was anywhere near Wigan, to accompany the Colonel to St. John’s. A very distinguished Irish prelate would also have been present that evening. So you see this disastrous war has caused many disappointments. I have said Colonel O’Leary was a credit to his profession. One account from the seat of war says : “The way in which the South Lancashire Regiment has been handled during the operations in Natal stamps their late commander as a tactician of no mean ability.” It is a pleasure to us Irishmen to know there are three gallant Irish Catholic generals in the field at present, and 25,oco Irish Catholic soldiers. Two of these generals were educated like Colonel MacCarthy O’Leary in Jesuit Colleges, and at the present moment one of the Colonel’s sons is at Stonyhurst, and another is at Sandhurst. There were and are several old college companions of Colonel O’Leary engaged in the war, and by a coincidence it was from another Stonyhurst boy that there came, in the name of the Sultan of Tutkey, in the hour of victory, a telegram of congratulotions from Sir Nicholas O’Connor our Ambassador at Constantinople. The men of the South Lancashire Regiment, another account says, idolised their colonel, he was more like a father to them than their commanding officer. When marching through the streets of Preston, a few months ago, his men were heard shouting “We’ll die for our old Colonel.” All this must mean that very close and even affectionate relations subsisted between their good leader and his devoted followers. One more incident will serve to clinch, I take it, these statements. When the South Lancashires were under orders to move from the last station, Fermoy, or Clonmel, I forget which—I am told the Colonel went personally to the Horse Guards where, as in other places, he was a great favourite, and begged earnestly that the regiment should not be sent to a certain city for which It was under orders, but that they might be sent to Preston where they would be exposed to fewer temptations. You know he gained his request. And now about his religion. I am sorry we could not all be present at the Requiem sung for his soul at the Church of the English Martyrs last week. I am told that when, after the Absolutions at the catafalque, the bugles rang out and drums rolled, there were few eyes dry in that immense congregation. For here men felt that they were parting with a good Catholic, and we live in days when we need the example of good Catholics, especially in the high places. It requires, of course, a certain amount of moral courage, a very different thing from physical courage, to be a practical Christian in these days’s of scepticism and rationalism. So we cannot help in the in front of the man to admire him when we find him in the “crowd of “doubting Thomases and careless Gallios.” An enthusiastic and zealous Catholic, but, no zealot, one could not for many minutes converse with Colonel O’Leary without perceiving he was a man of deep religious conviction, a stern believer in the supernatural and unseen world, and a man who though far from wishing to thrust his religion down the throats of others, was as ready to die for his own, as he did actually die for his country. I repeat his religion was not that of the professional but of the practical turn. He readily recognised that there are times and places when we should all be ready to openly give expression to the faith that is in us. And withal he was of a retiring disposition, and preferred to act rather than talk. I May be allowed to give one illustration of this. You may remember last year we had a visit from one of her Majesty’s Judges of the High Court—another practical and exemplary Catholic—who happened to be holding the assizes at Manchester. I mentioned the circumstance in a letter to Colonel M’Carthy O’Leary, and invited him to come over, and suggested that as the Mayor of Wigan was going to give the Judge an official reception at the station, he (the Colonel) might come in uniform, and I also requested him to invite any other Catholic officer who might be free to accompany him. This is his reply by return of post : “Dear Father Hayden, I shall be very glad indeed to assist in your reception of Judge Day, and thank you very much for your kind invitation for Wednesday evening, the 8th inst., at St. John’s, Wigan. The only other Catholic officer in my regiment, Mr. Kane, will accompany me unless duty Should prevent him. You know what that means—like yourselves, Jesuit Fathers, we have to do what we are told, and cannot be certain of our movements so far in advance.. I am sure the reception will be all that you would desire, and worthy of that great and good Judge Day. Uniform of course, especially as Mr. Mayor will be present in his official capacity. Believe me, dear Father Hayden, yours sincerely, W. M’Carthy O’Leary.” Well, you all remember the sensation his stately and picturesque form made in the town. May I tell you another incident of that night ? It will further illustrate his humility, and his belief in the value of deeds rather than words. On the platform I said : “Now, Colonel,I know that at dinner I promised you should not be called upon for a speech, but several people here in the public hall are hoping you will saya few words, if only replying to the vote of thanks to our visitors.” “No, father,” he said, “please do not insist, deeds are more in our line than words.” And though he could speak, and speak well, you never heard him in Wigan. In passing, I may remark that two out of the ten or twelve men on the platform that might have passed suddenly away. Dr. Stuart, I believe, was found lately dead in his bed ; our Colonel died on the battlefield at the head of his regiment. “Deeds, not words are more in our line.” He was coming to be chairman at one of our lectures in St. John’s Hall, and this is the humble way he regards the invitation : “Preston, December 2, 5898, Dear Father Hayden,— It will always be a sincere pleasure to me to be of any possible service to a Jesuit father. I only hope my taking the chair at the lecture you write of in January next will be a service ! And I respectfully suggest some local magnate instead of a soldier who hails from the dear old County of Cork. I know that you have been associated with soldiers, so you will know that we are not allowed, and very properly so, to take any part in politics, so I presume the lecture you write of will be of a purely nonpolitical charcter. Perhaps you will reconsider your selection of a chairman as I suggest, and be assured that should you consider such advisable I shall still consider myself very flattered in having been thought of by you.” I could give many more examples of his zeal, but I have, I find, come to the end of this paper, and probably the time, too. The band of the South Lancashire Regiment was at the Stonyhurst Academy last summer. It played at the public hall, Preston, a few months ago, also at a concert on behalf of the Society of St. Vincent of Paul, which society is doing in Preston a grand work for the poor. Bazaars were utterly distasteful to him, and yet we find him opening one in Blackpool, and his necessary short speech on that occasion is taken up with the expression of his joy and surprise at finding such beautiful churches and excellent schools in Blackpool. Again on the eve of his departure for the war he is down to accompany his good lady to open a bazaar at Chorley, but his duty kept him in Preston, and Mrs. M’Carthy O’Leary went alone to keep her promise. And how did this good man meet his end ? Unprepared ? No! God forbid ! God takes care of those who do not fear to confess Him before men. This upright man, this fearless Catholic, this affectionate father and husband, this man most popular in his club, and, loved by his men, took an interest in their spiritual welfare, as well as in their temporal welfare. With over one hundred of his men he approached the Sacraments of Confession and Holy Communion ; and we find him with the Catholic men of his regiment attending a retreat during the week before their departure for the war, preached, at his request, in the Church of the English Martyrs by his friend, Father Bernard Vaughan, S.J. A letter just to hand from a non-Catholic soldier tells us that every night during the voyage to South Africa Colonel M’Carthy O’Leary assembled his co-religionists, and together with them piously recited the Rosary. The death of such a man, if sudden, was not unprovided for.

– from The Tablet (Page 38, 5th October 1901)

=======

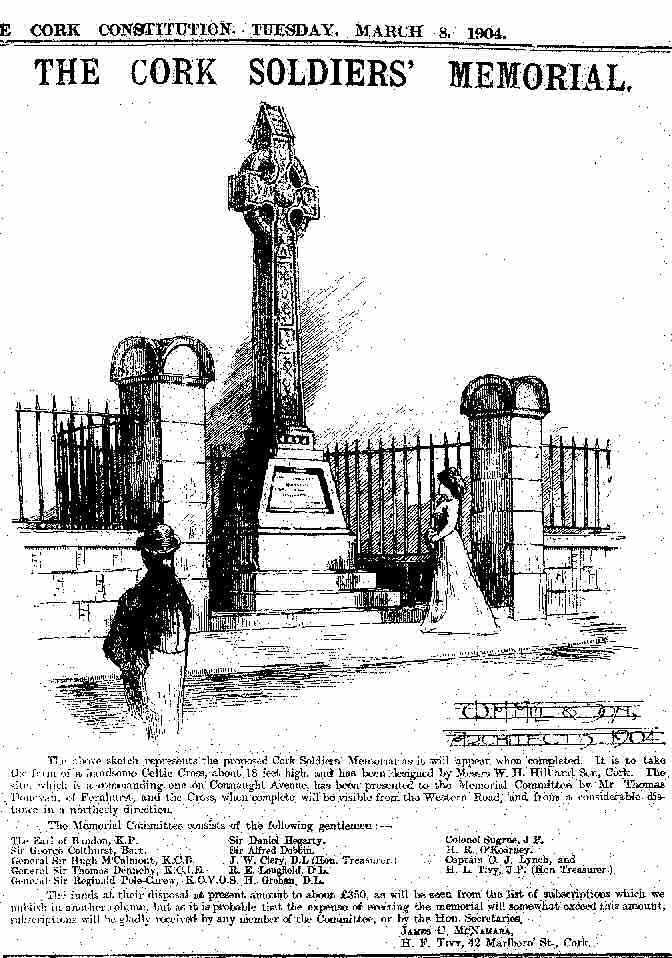

Boer War Memorial in Cork

The Boer War Memorial in Cork City is at the end of Connaught Avenue. Erected in 1904, it commemorates all those from Cork who list their lives in that South African War. William McCarthy-O’Leary is the first name on the memorial which reads:

“ERECTED BY PUBLIC SUBSCRIPTION IN MEMORY OF THE OFFICERS, NON-COMMISSIONED OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE COUNTY AND CITY OF CORK

WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE SERVICE OF THE EMPIRE DURING THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAR 1899-1902

LT. COL. W. M. CARTHY O’LEARY SOUTH LANCASHIRE REGT.

…”

The memorial is located at the end of Connaught Avenue (just off College Road), and looks out over the River Lee and the north side of Cork City. Over the years, the memorial has been damaged and defaced, thus the railing all around it now. The “O’Leary” part of William McCarthy-O’Leary seems to have been beaten off at some stage too.

[Google Street View] [Memorial text] [Irish War Memorials]

=======

Links:

Unveiling of the Statue … from Warrington Through Time (Google Books)

Family Tree / Peerage … from ThePeerage.com

The Statue is located in Queen’s Gardens, Palmyra Square N, Warrington WA1 1BW, UK ( Map: 53.387778, -2.596557)

The Warrington Boer War Memorial … roll-of-honour.com

Lt Col MacCarthy O’Leary W … 1st Battalion South Lancs

===========

TODO: move this to a new article of its own … also do a McCarthy O’Leary Family tree like the Wallis

His Mother Jane Frances O’Connell

From 20 April 1830, her married name became O’Donoghue. From 29 October 1839, her married name became McCarthy-O’Leary.1

Child of Jane Frances O’Connell and John McCarthy-O’Leary

- Lt.-Col. William McCarthy-O’Leary+ d. 27 Feb 1900

Child of Jane Frances O’Connell and Charles James O’Donoghue, The O’Donoghue of the Glens

- Daniel O’Donoghue, The O’Donoghue of the Glens+2 b. 11 May 1831, d. 2 Oct 1889

Death of Jane McCarthy-O’Leary of Coomlagane, widow, 84 yrs old, widow of John McCarthy-O’Leary J.P. and deputy Lieutenant, senile decay 10 days

Jane’s Father John O’Connell was born on 6 May 1778.1 He was the son of Morgan O’Connell and Catherine O’Mullane.2 He married Elizabeth Coppinger, daughter of William Coppinger, in February 1806.1 He died on 6 September 1853 at age 75 at Dinan, FranceG.1

He lived at Grenagh, Killarney, County Kerry, IrelandG.1

Children of John O’Connell and Elizabeth Coppinger

- Catherine O’Connell2

- Morgan John O’Connell+2 b. 27 Aug 1811, d. 2 Jul 1875

- Jane Frances O’Connell+2 b. c 1812, d. 15 Mar 1897

- Maurice John O’Connell2 b. 1819, d. 22 Nov 1836

- Reverend John Dominic Patrick O’Connell2 b. 25 Mar 1828, d. 15 Jun 1872